Meat Science

Meathead

Meat is cut from the muscles of mammals and birds. For some reason, fish muscle is not considered meat by some people, but it should be. It is fish muscle tissue.

On average, lean muscle tissue of mammals typically breaks down like this: Water (about 75%), protein (18%), fats (5%), carbohydrates, salt, vitamins, sugars, and minerals (2%).

Muscle cells

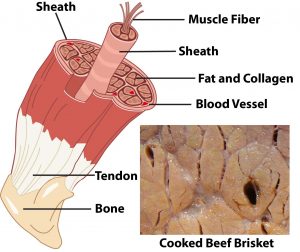

Muscle cells are more frequently called muscle fibers because they are shaped like tubes. Muscle fibers bundled together are called sheaths, and sheaths bundled together are called muscle or meat.

The fibers, about the thickness of a human hair, contain several types of protein, among them myosin and actin which bind up water and act like living motors by contract-ing and relaxing on command by nerves. As an ani-mal ages, grows, and exercises, its muscle fibers get thicker and tougher.

Myoglobin is another important protein in muscle fibers. Myoglobin receives oxygen and iron from hemoglobin in blood, fuel necessary for muscles to function. Myosin and actin are not water soluble, but myoglobin is water solu-ble, and myoglobin is the protein in meat that makes it appear red.

That’s right, the reddish color in meat and its juices is not caused by blood. It is myoglobin dissolved in water, called myowater. Myoglobin is found only in muscle, not in the blood stream. The blood is pretty much all drained out in the slaughterhouse. If the stuff on your plate when you sliced a steak was blood, it would be much darker, like human blood, and it would coagulate, like human blood. If the fluids were blood, then pork and chicken would be dark red. It’s mostly just water.

So let’s stop grossing out our kids, and just call it juice. OK? Every time you call meat juices blood, a bell rings and a teenager be-comes a vegan.

On average, beef has 8 milligrams of myoglobin per gram of meat, according to the meat scientists at Texas A&M University’s De-partment of Animal Science, making it one of the darkest red meats. Lamb has about 6 milligrams per gram, pork about 2 mg/g, and chicken breast about 0.5 mg/g. If pork is the other white meat, lamb is the other red meat. When warmed, meat juices con-taining myoglobin lose their red color, become lighter pink, and eventually tan or gray.

Most of the liquid in meat is water. When animals are alive, the pH of the muscle fibers is about 6.8 on a scale of 14. The lower the number, the higher the acidity. The higher the number, the more alkalinity and less acidic. At 6.8, living muscle is just about neu-tral. When the animal dies, the pH declines to about 5.5, making it acidic. At this pH, muscle fibers form bunches and squeeze out juice, called purge, and that is the juice you see in packages of meat that is absorbed by the diapers that butchers put under the meat.

Muscle fibers also contain other proteins, notably, enzymes. En-zymes play an important role in aging meat.

Connective tissue

Connective tissue is most obvious in the form of tendons that connect muscles to bones and in ligaments that connect bones to other bones. It is also visible as the thin shiny sheathing that wraps around muscles called silverskin or fascia. These tougher, chewier, rubberband-like connective tissues are mostly collagen and elastin (as opposed to the muscle, which is mostly myosin.) We call them gristle and they shrink when heated and become hard to chew. As with muscle fibers, connective tissues thicken and toughen as an animal exercises and ages.

A softer connec-tive tissue called collagen is scat-tered throughout the muscle, often surrounding fibers and sheaths hold-ing them together. And yes, this is pretty much the same stuff the ac-tors have injected into their faces to get rid of wrinkles.

When you cook, collagen melts and turns to a rich liquid called gelatin, similar to the stuff Jell-O is made from. Cooked muscle fibers, no longer bound together by collagen, are now uniformly coated with a soft, gelatinous lubricant. This smooth and sensual substance enrobes meat in a wonderfully silken texture and adds moisture.

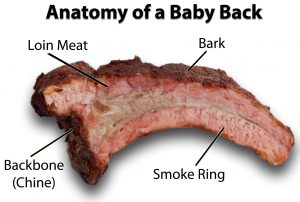

Lean meats such as beef or pork tenderloin, as well as most chicken and turkey, don’t have much collagen. When cooking tough cuts of meat with lots of connective tissue, like ribs, brisket, and shoulder, it is important to liquefy the meat’s connective tis-sue into gelatin: that’s what makes these tough meats taste ten-der. This takes time. That’s why these cuts are often cooked low and slow.

Muscle fibers start seizing up around 125°F to 140°F if heated quickly. But when heated slowly, the rubber band-like connective tissues have time to relax and do not squeeze tightly. In general, we believe it is best to cook all meats at about 225°F. Slow roast-ing does wonders for meat. The AmazingRibs.com science advisor Prof. Greg Blonder says “Think of silly putty. Pressed hard and quickly, it acts like a rigid solid. Pressed slowly, it flows.” When heated slowly, the muscle fibers, instead of wringing out mois-ture, relax and simply let water linger inside until evaporation drives it out.

After it melts, as it chills, gelatin can solidify into that jiggly stuff which, with a little filtering, can then be called aspic and served at bridge clubs. Here’s a pot of the stuff made simply by boiling a couple of chicken carcasses in water after I ate the meat, dis-carded the bones, and chilled the liquid. The white is fat, most of which I have removed, and the tan is jiggly gelatin.

Fats

Fats (lipids) and oxygen are the main fuels that power muscles. Fats are packed with calories, which are potential energy released when the chemical bonds are broken. From a culinary standpoint, fat comes in three types:

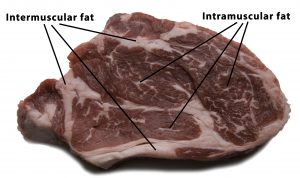

• Subcutaneous fats are the thick hard layers beneath the skin.

• Intermuscular fats are layers between muscle groups.

• Intramuscular fats woven amongst the muscle fibers and sheaths improve meat’s moisture, texture, and flavor when cooked. These threads of intramuscular fat are called marbling because they have a striated look similar to marble.

Large fat deposits can also be found around organs, especially kidneys. On hogs, the best fat of this type, at least from a culinary standpoint, especially if you make pie crusts, is called leaf lard, and it comes from around the kidneys. Fats are crucial to meat texture. Waxy when cold, fats start to melt around 130°F to 140°F, lubricating muscle fibers just as they are getting tougher and drier from the heat. Fat does not evaporate like water when you are cooking.

Fat also provides much of the flavor in meat. It absorbs and stores many of the aromatic compounds in the animal’s food. As the ani-mal ages, those flavor compounds build up and get more notice-able. After the animal is slaughtered, the fat can turn rancid if stored too warm, too long, or in contact with oxygen. So we have a tradeoff. The muscle fibers and connective tissues get tougher as the animal ages and exercises, while the fat accumulates and builds flavor.

Fats, especially animal fats, are the subject of great debate among scientists, doctors, dietitians, and health faddists. For many years, animal fats were thought to be dangerous and avoided. It is now thought that fats, even animal fats, contain many beneficial com-ponents, and current science argues that, in moderation, they are essential for health. A great deal of interesting research on the subject is going on as we write this. A great deal of research is contradictory. Read more about what we have learned about food and health in this article.

Slow twitch vs. fast twitch muscles

Muscle fibers need fat and oxygen for fuel. Fat comes from fatty acids in the animal’s blood that were created by digestion of its food. Oxygen is carried by the protein hemoglobin in the blood-stream, and it hands the oxygen to myoglobin within the muscles.

In general, the more exercise a muscle gets, the tougher it is, and the more oxygen-laden myoglobin it needs. Myoglobin turns meat darker and makes it more flavorful. Dark meats, like beef, lamb, duck, and goose, are made of “slow twitch” muscles that have evolved to endure slow, steady movement, and they are loaded with juicy myoglobin. Dark meats also have more fat for energy.

White meats, like chicken breasts, are mostly “fast twitch” muscles, which are better suited to brief bursts of energy, and they have less myoglobin. Chicken legs are slow twitch, and even though they are not red, they are darker than breasts. When cooked, the slow twitch muscles in dark meat have more moisture and fat and are more flavorful than white meat. White meats contains less moisture and fat, and they dry out more easily when cooked. Poultry gets more exercise standing and walking than flying, so the legs and thighs have lots of slow-twitch muscles, more pigment, more juice, more fat, and more flavor. They are also slightly more forgiving when cooked. Modern chickens and turkeys have been bred for large breasts because white meat is more popular in this country (and we can’t understand why). We’ll take tough and flavorful over tender and mild any day.

Ducks and geese excel at flying and swimming, and they get more exercise than chickens and turkeys, so these birds have more dark meat. Duck and goose breasts are deep purple, almost the same color as lamb or beef.

When the conventional wisdom was that dietary fat could cause heart and arterial problems, domestic pigs were bred to have less intramuscular fat. The modern pig does not get much exercise due to its transmogrification into “the other white meat.” In recent years, research has questioned the relationship between dietary fat and health, and many experts now extol fat’s benefits.

Beef is all pretty much the same color, but slow twitch muscles like flank steak have bigger, richer flavor than some of the lesser used muscles like tenderloin.

Fish live in a practically weightless environment, so their muscles are very different. Fish muscles have very little connective tissue, and that’s one reason why fish never gets as tough as pork when cooked. But fish can dry out because there is not much collagen to moisturize the muscle fibers. The color and texture of fish varies depending on the life it leads. Small fish that swim with quick darting motions have mostly fast-twitch muscles and white meat, while flounder, which lives on the sea floor, has delicate flaky flesh. Torpedos like tuna and swordfish swim long distances with slow steady tail movements, so they have have firmer, darker, sometimes even red flesh. For these reasons and others, fish can spoil within days of being caught, while red meats keep much longer.

Brown is beautiful, black is bad

As meat cooks, the most magical transformation that occurs is the Maillard reaction. It is named for a French scientist who discov-ered the phenomenon in the early 1900s. The surface turns brown and crunchy and gets ambrosial in aroma. Who doesn’t love the crispy exterior of a slice of roast beef, the browned crust on freshly baked bread? We don’t think twice about it, but that brown color on the surface is the mark of hundreds of compounds cre-ated when heat starts changing the shape and chemical structure of the amino acids, carbohydrates, and sugars on the surface of the meat. If there is sugar in the rub or marinade it can undergo a flavorful transformation called caramelization. Click here to learn more about the Maillard reaction and caramelization.

What you don’t want is black meat. Let it go too far and it turns to carbon. Carbonized meat may be unhealthy.

Pretty in pink

There’s another color you may notice in cooked meat: Pink. Many smoked meats turn bright pink just under the surface. Some peo-ple think that pink color means that meat is raw, but not in this case. If the meat were undercooked, the pink would be in the cen-ter, not just below the surface. Pink meat near the surface is a common phenomenon called the smoke ring and it is caused by gases in smoke preserving the color of myo-globin. Some people think the smoke ring improves taste. That’s a myth too. Click here to read more about the smoke ring and what causes it.

Meathead is the barbecue whisperer who founded AmazingRibs.com, by far the world’s most popular outdoor cooking website. He is the author of “Meathead, The Science of Great Barbecue and Grilling,” a New York Times Best Seller that was also named one of the “100 Best Cookbooks of All Time” by Southern Living magazine. This article was excerpted and modified from his book and website. For 2,000+ free pages of great barbecue and grilling info, visit AmazingRibs.com and take a free trial in the Pitmaster Club.

Originally it started as a printed newsletter to let avid barbecuers keep track of upcoming events and results from past events. Today we have evolved into a barbecue and grilling information super highway as we share information about ALL things barbecue and grilling.

© 2022 National Barbecue News: Designed by ThinkCalico